Julia de Vries, QUT Psychology (Honours) Student.

The global market for robotics is projected to reach more than $160 billion USD by 2030 (Boston Consulting Group, 2021). As Artificial Intelligence (AI) products like ChatGPT are made readily available to anyone with internet access, consumer interest and demand continues to grow. With this increased interest, robots and AI products have become a key focus of ethical and regulatory conversations.

Dr Kate Letheren explored these questions in a presentation to the Department of Transport and Main Roads’ (TMR) Customer Research Community of Practice on 30 March, 2023. The Community of Practice shares customer research insights to support TMR to understand and address changing customer needs and expectations for TMR and the transport network.

Dr. Letheren proposed the following four “rules” for robots, based on consumer research.

Rule number 1. Robots are not allowed to be the boss of me (unless I allow it)

While many consumers are open to using robots to complete a range of tasks, less are willing to compromise on their own autonomy (Letheren, Russell-Bennett, Mulcahy & McAndrew, 2019). In other words, we’d like robots to do the groundwork, but come to us for guidance when reaching a decision point.

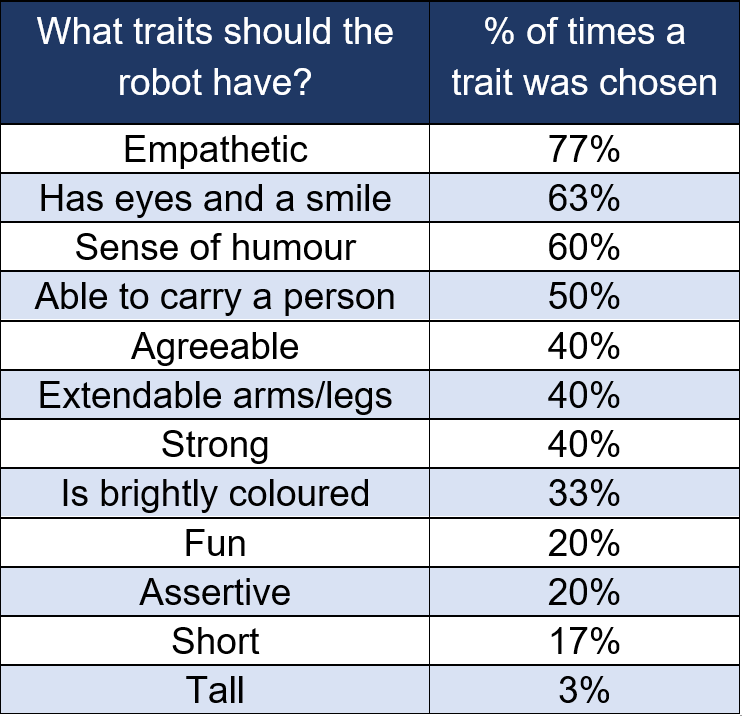

During the presentation, Dr Letheren asked attendees to imagine they were designing a robot to assist older people with mobility. Attendees were given 12 traits and asked to choose ones that they thought the robot should have (they could choose multiple traits). In line with rule 1, attendees tended to select amiable traits, such as empathetic (77%), and agreeable (40%), over more directive and powerful traits, such as assertive (20%) and tall (3%).

Rule number 2. Robots should be ready to socialise with me, but only if I feel like it

Research has shown that consumers want the assistance of service robots to do tasks, but they don’t necessarily want to socialise with them. Considering this, one recommendation for high-contact service robots is that they should offer the option for social contact and allow consumers to decide if, and when they want to socialise with the robot (Letheren, Jetten, Roberts & Donovan, 2021).

Dr Letheren noted that socialising may seem like an odd choice of words when describing interactions with robots, but indeed many robots and AI agents are intentionally designed to interact with humans in a social way. One way of encouraging consumers to interact with AI agents is to provide them with a human-like appearance. Consumers typically prefer robots and AI that resemble humans. This was demonstrated in our session exercise, with the second most frequently chosen trait being ‘has eyes and a smile.’Designing a robot or AI agent to look human can encourage anthropomorphism—a phenomenon in which consumers project human characteristics onto non-human agents (Epley et al., 2007). Remember Clippy? Or ever really considered the Amazon logo? These are both examples of companies designing products to make the most of our anthropomorphising tendencies.

Rule number 3. It’s better to take from robots than humans

A study by Dootson et al. (2022) compared how likely people are to keep money given to them in error when interacting with an ATM, a robot, and a human. They found that participants were more likely to keep the money when it was provided to them by an ATM, followed by a robot, and then a human. The results of the study suggest that there may be some positives to designing human-like robots.

Rule number 4. I’ll trust a robot more if I have a hand in designing it

Consumers often demonstrate a preference for robots that they’ve had input into designing, potentially an example of the IKEA effect where we tend to value self-made products more (Norton et al., 2012). After participants had considered the traits that they would want in a robot designed to assist an elderly person with mobility issues, Dr Letheren presented them with the question “Imagine it is now many years in the future and you are entering your own ‘aging in place’ stage. Which robot will you order?” Participants selected one of three response options, being: “I want the robot I designed (or the upgraded version)“; “Any robot that meets my needs will be fine“; or “No robots for me, I prefer a human“.

Interestingly, 30% of participants indicated they would purchase the robot they designed, with 39% being open to any robot that met their needs, and 30% preferring a human. Maybe we just didn’t trust our design skills!

New rules are emerging all the time

As new tasks and roles are implemented, new rules continue to emerge for robots. With these new rules, it is important to consider the ethical development and regulation of robots and AI. This industry is constantly developing—so stay tuned!

References

Boston Consulting Group (2021, June 28). Robotics Outlook 2030: How intelligence and mobility will shape the future. Retrieved May 12, 2023 from: https://www.bcg.com/publications/2021/how-intelligence-and-mobility-will-shape-the-future-of-the-robotics-industry

Buckley, N. (2016, March 27). Racist AI behaviour is not a new problem. Retrieved April 3, 2023, from https://natbuckley.co.uk/2016/03/27/racist-ai-behaviour-is-not-a-new-problem/

Chandler, J., & Schwarz, N. (2010). Use does not wear ragged the fabric of friendship: Thinking of objects as alive makes people less willing to replace them. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 20(2), 138-145.

Dootson, Paula, Greer, Dominique A., Letheren, Kate, & Daunt, Kate L. (2023) Reducing deviant consumer behaviour with service robot guardians. Journal of Services Marketing, 37(3), pp. 276-286.

Epley, N., Waytz, A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2007). On seeing human: A three-factor theory of anthropomorphism. Psychological review, 114(4), 864.

Letheren, K., Jetten, J., Roberts, J., & Donovan, J. (2021). Robots should be seen and not heard… sometimes: Anthropomorphism and AI service robot interactions. Psychology & Marketing, 38(12), 2393-2406.

Letheren, K., Russell-Bennett, R., Mulcahy, R., & McAndrew, R. (2019). Control, cost and convenience determine how Australians use the technology in their homes. The Conversation, 9.

Norton, M. I., Mochon, D., & Ariely, D. (2012). The IKEA effect: When labor leads to love. Journal of consumer psychology, 22(3), 453-460.

Tam, K. P., Lee, S. L., & Chao, M. M. (2013). Saving Mr. Nature: Anthropomorphism enhances connectedness to and protectiveness toward nature. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 49(3), 514-521.

Waytz, A., Heafner, J., & Epley, N. (2014). The mind in the machine: Anthropomorphism increases trust in an autonomous vehicle. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 52, 113-117.