July 30

- Frank M. Snowden (2019). Epidemics and Society: From the Black Death to the Present.

- Not quite “to the present” as we have been experiencing with COVID-19,12 but timely nonetheless. A history book that not only examines a series of ghastly biological disasters, but also discusses public health strategies, how epidemic diseases have played a leading role in the development of biomedical paradigms of disease, maps public responses, and explores the relation war and disease. You can also watch his Yale lectures on Epidemics in Western Society Since 1600 here.

- Jared Diamond (2019). Upheaval: How Nations Cope with Crisis and Change.

- Diamond’s latest contribution and an attempt to understand how nations deal with crises. Blurb: In a riveting journey into the recent past, he traces how six countries have survived defining catastrophes – from the forced opening of Japan to the Soviet invasion of Finland to Chile’s brutal Pinochet regime – through selective change, a coping mechanism more commonly associated with personal trauma. Looking ahead to the gravest threats we face in the future, he asks, what can we learn from the lessons of the past?

- Steven Levitsky and Daniel Ziblatt (2018). How Democracies Die: What History Reveals About Our Future.

- Introduction: “American politicians now treat their rivals as enemies, intimidate the free press, and threaten to reject the results of elections. They try to weaken the institutional buffers of our democracy, including the courts, the intelligence services, and ethics offices. America may not be alone. Scholars are increasingly concerned that democracy may be under threat worldwide – even in places where its existence has long been taken for granted. Populist governments have assaulted democratic institutions in Hungary, Turkey, and Poland. Extremist forces have made dramatic electoral gains in Austria, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and elsewhere in Europe. And in the United States, for the first time in history, a man with no experience in public office, little observable commitment to constitutional rights, and clear authoritarian tendencies was elected president. What does all of this mean? Are we living through the decline and fall of one of the world’s oldest and most successful democracies? (p. 2)”

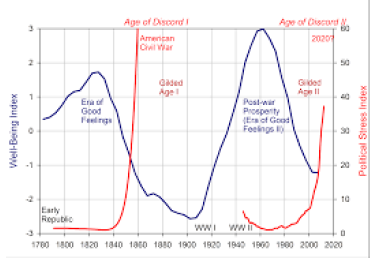

- Peter Turchin (2016). Ages of Discord: A Structural-Demographic Analysis of American History.

- Turchin, the father of cliodynamics16 is discussed in David Sloan Wilson’s This View of Life17. “Turchin is a biologist and the son of the Russian physicist and dissident Valentine Turchin. Peter immigrated to America with his father in 1978 and became a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Connecticut, specializing in population dynamics. Many species in nature fluctuate in their numbers, with booms and busts that sometimes take the form of regular cycles and at other times are more chaotic. These fluctuations reflect complex interactions with other species in the community, along with exogenous factors such as climate. … Peter was among the best but when he reached midlife he decided that he needed a new challenge. He would apply his theoretical and statistical skills to the study of human history. In a single stroke, Peter had isolated himself from almost everyone at his university and the wider world of academia. His colleagues in the Department of Ecology and Evolution never dreamt of studying human history and those in other departments who studied human history never dreamt of employing his theoretical and statistical toolkit” (p. 181). Now check the lines. Are we again on the brink of an Age of Discord?

- Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt (2018). The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up A Generation for Failure.

- According to the authors, this is a book about wisdom and its opposite: “We had been writing about some ideas spreading through universities that we thought were harming students and damaging their prospects for creating fulfilling lives. These ideas were, in essence, making students less wise. So we decided to write a book to warn people about these terrible ideas, and we thought we’d start by going on a quest for wisdom ourselves” (p. 1).

- Mikael Klintman (2019). Knowledge Resistance: How We Avoid Insights from Others.

- Goal of the book: To understand, rethink, and handle problematic cases in which people resist the insights of others. Klintman: “[W]e need to consider treating such resistance as the multifaceted and profoundly human phenomenon it is” (p. 9).

- Justin E. H. Smith (2019). Irrationality: A History of the Dark Side of Reason

- Introduction: “For the past few millennia, many human beings have placed their hopes for rising out of the mess we have been born into – the mess of war and violence, the pain of unfulfilled passions or of passions fulfilled to excess, the degradation of living like brutes – in a single faculty, rumored to be had by all and only members of the human species… We call this faculty ‘rationality,’ or ‘reason.’ Any triumph of reason, we might be expected to understand these days, is temporary and reversible. Any utopian effort to permanently set things in order, to banish extremism and to secure comfortable quiet lives for all within a society constructed on rational principles, is doomed from the start. The problem is, again, evidently of a dialectical nature, where the thing desired contains its opposite, where every earnest stab at rationally building up society crosses over sooner or later, as if by some natural law, into an eruption of irrational violence. The harder we struggle for reason, it seems, the more we lapse into unreason… This book proceeds through an abundance of illustrations and what are hoped to be instructive ornamentations, but the argument at its core is simple: that it is irrational to seek to eliminate irrationality, both in society and in our own exercise of our mental faculties. When elimination is attempted, the result is what the French historian Paul Hazard memorably called la Raison aggressive, ‘aggressive Reason’ (pp. 5-6).

- Andrew Marantz (2019). Antisocial: Online Extremists, Techno-Utopians, and the Hijacking of the American Conversation.

- “This is not a book arguing that the fascists have won, or that they will win. This is a book about how the unthinkable becomes thinkable. I don’t assume that America is destined to live up to its founding ideals of liberty and equality. Nor do I assume that it is doomed to repeat its founding reality of brutal oppression. I can’t know which way the arc will bend. What I can offer is the story of how a few disruptive entrepreneurs, motivated by naïveté and reckless techno-utopianism, built powerful new systems full of unforeseen vulnerabilities, and how a motley cadre of edgelords, motivated by bigotry and bad faith and nihilism, exploited those vulnerabilities to hijack the American conversation”. A book recommended by Murray Scott.

- Anne Case and Angus Deaton (2020). Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism

- Preface: “This book [compared to the The Great Escape] is much less upbeat. It documents despair and death, it critiques aspects of capitalism, and it questions how globalization and technical change are working in America today. Yet we remain optimistic. We believe in capitalism, and we continue to believe that globalization and technical change can be managed to the general benefit. Capitalism does not have to work as it does in America today. It does not need to be abolished, but it should be redirected to work in the public interest. Free market competition can do many things, but there are also many areas where it cannot work well, including in the provision of healthcare, the exorbitant cost of which is doing immense harm to the health and wellbeing of America. If governments are unwilling to exercise compulsion over health insurance and to take the power to control costs—as other rich countries have done—tragedies are inevitable. Deaths of despair have much to do with the failure—the unique failure—of America to learn this lesson” (p. ix).

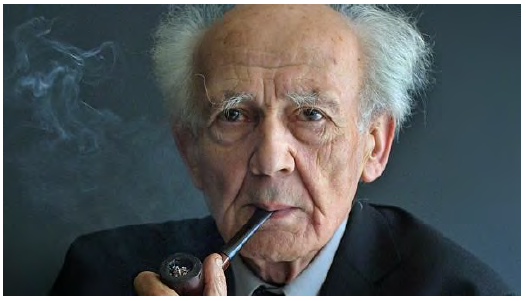

- Tomáš Sedláček (2011). Economics of Good and Evil: The Quest for Economic Meaning from Gilgamesh to Wall Street.

- Václav Havel in his Foreword: “What is economics? What is its meaning? Where does this new religion, as it is sometimes called, come from? What are its possibilities and its limitations and borders, if there are any? Why are we so dependent on permanent growing of growth and growth of growing of growth? Where did the idea of progress come from, and where is it leading us? Why are so many economic debates accompanied by obsession and fanaticism? All of this must occur to a thoughtful person, but only rarely do the answers come from economists themselves”. A book suggestion provided by Imke Lammers.

- John Tierney and Roy F. Baumeister (2019). The Power of Bad: How the Negativity Effect Rules Us and How We Can Rule It.

- Prologue: “Take the bad with the good, we stoically tell ourselves. But that’s not how the brain works. Our minds and lives are skewed by a fundamental imbalance that is just now becoming clear to scientists: Bad is stronger than good. This power of bad goes by several names in the academic literature: the negativity bias, negativity dominance, or simply the negativity effect. By any name, it means the universal tendency for negative events and emotions to affect us more strongly than positive ones. We’re devastated by a word of criticism but unmoved by a shower of praise. We see the hostile face in the crowd and miss all the friendly smiles. The negativity effect sounds depressing—and it often is—but it doesn’t have to be the end of the story. Bad is stronger, but good can prevail if we know what we’re up against. By recognizing the negativity effect and overriding our innate responses, we can break destructive patterns, think more effectively about the future, and exploit the remarkable benefits of this bias. Bad luck, bad news, and bad feelings create powerful incentives—the most powerful, in fact—to make us stronger, smarter, and kinder. Bad can be put to perfectly good uses, but only if the rational brain understands its irrational impact. Beating bad, especially in a digital world that magnifies its power, takes wisdom and effort” (p. 9).

- Philip Zimbardo (2008). The Lucifer Effect: Understanding How Good People Turn Evil.

- Zimbardo, the creator of the Stanford Prison Experiment: “In reflecting on the reasons that I have spent much of my professional career studying the psychology of evil—of violence, anonymity, aggression, vandalism, torture, and terrorism—I must also consider the situational formative force acting upon me. Growing up in poverty in the South Bronx, New York City, ghetto shaped much of my outlook on life and my priorities. Urban ghetto life is all about surviving by developing useful “street-smart” strategies. That means figuring out who has power that can be used against you or to help you, whom to avoid, and with whom you should ingratiate yourself. It means deciphering subtle situational cues for when to bet and when to fold, creating reciprocal obligations, and determining what it takes to make the transition from follower to leader” (xi).

- Zygmunt Bauman (2007). Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty.

- Bravely into the Hotbed of Uncertainty: “At least in the ‘developed’ part of the planet, a few seminal and closely interconnected departures have happened, or are happening currently, that create a new and indeed unprecedented setting for individual life pursuits, raising a series of challenges never before encountered. First of all, the passage from the ‘solid’ to a ‘liquid’ phase of modernity: that is, into a condition in which social forms (structures that limit individual choices, institutions that guard repetitions of routines, patterns of acceptable behaviour) can no longer (and are not expected) to keep their shape for long, because they decompose and melt faster than the time it takes to cast them, and once they are cast for them to set. Forms, whether already present or only adumbrated, are unlikely to be given enough time to solidify, and cannot serve as frames of reference for human actions and long-term life strategies because of their short life expectation: indeed, a life expectation shorter than the time it takes to develop a cohesive and consistent strategy, and still shorter than the fulfilment of an individual ‘life project’ requires. Second, the separation and pending divorce of power and politics, the couple that since the emergence of the modern state and until quite recently was expected to share their joint nation-state household ‘till death did them part’. Much of the power to act effectively that was previously available to the modern state is now moving away to the politically uncontrolled global (and in many ways extraterritorial) space; while politics, the ability to decide the direction and purpose of action, is unable to operate effectively at the planetary level since it remains, as before, local. The absence of political control makes the newly emancipated powers into a source of profound and in principle untameable uncertainty, while the dearth of power makes the extant political institutions, their initiatives and undertakings, less and less relevant to the life problems of the nation-state’s citizens and for that reason they draw less and less of their attention. Between them, the two interrelated outcomes of the divorce enforce or encourage state organs to drop, transfer away, or (to use the recently fashionable terms of political jargon) to ‘subsidiarize’ and ‘contract out’ a growing volume of the functions they previously performed. Abandoned by the state, those functions become a playground for the notoriously capricious and inherently unpredictable market forces and/or are left to the private initiative and care of individuals. Third, the gradual yet consistent withdrawal or curtailing of communal, state-endorsed insurance against individual failure and ill fortune deprives collective action of much of its past attraction and saps the social foundations of social solidarity; ‘community’, as a way of referring to the totality of the population inhabiting the sovereign territory of the state, sounds increasingly hollow. Interhuman bonds, once woven into a security net worthy of a large and continuous investment of time and effort, and worth the sacrifice of immediate individual interests (or what might be seen as being in an individual’s interest), become increasingly frail and admitted to be temporary. Individual exposure to the vagaries of commodity-and-labour markets inspires and promotes division, not unity; it puts a premium on competitive attitudes, while degrading collaboration and team work to the rank of temporary stratagems that need to be suspended or terminated the moment their benefits have been used up. ‘Society’ is increasingly viewed and treated as a ‘network’ rather than a ‘structure’ (let alone a solid ‘totality’): it is perceived and treated as a matrix of random connections and disconnections and of an essentially infinite volume of possible permutations. Fourth, the collapse of long-term thinking, planning and acting, and the disappearance or weakening of social structures in which thinking, planning and acting could be inscribed for a long time to come, leads to a splicing of both political history and individual lives into a series of short-term projects and episodes which are in principle infinite, and do not combine into the kinds of sequences to which concepts like ‘development’, ‘maturation’, ‘career’ or ‘progress’ (all suggesting a preordained order of succession) could be meaningfully applied. A life so fragmented stimulates ‘lateral’ rather than ‘vertical’ orientations. Each next step needs to be a response to a different set of opportunities and a different distribution of odds, and so it calls for a different set of skills and a different arrangement of assets. Past successes do not necessarily increase the probability of future victories, let alone guarantee them; while means successfully tested in the past need to be constantly inspected and revised since they may prove useless or downright counterproductive once circumstances change. A swift and thorough forgetting of outdated information and fast ageing habits can be more important for the next success than the memorization of past moves and the building of strategies on a foundation laid by previous learning. Fifth, the responsibility for resolving the quandaries generated by vexingly volatile and constantly changing circumstances is shifted onto the shoulders of individuals – who are now expected to be ‘free choosers’ and to bear in full the consequences of their choices. The risks involved in every choice may be produced by forces which transcend the comprehension and capacity to act of the individual, but it is the individual’s lot and duty to pay their price, because there are no authoritatively endorsed recipes which would allow errors to be avoided if they were properly learned and dutifully followed, or which could be blamed in the case of failure. The virtue proclaimed to serve the individual’s interests best is not conformity to rules (which at any rate are few and far between, and often mutually contradictory) but flexibility: a readiness to change tactics and style at short notice, to abandon commitments and loyalties without regret – and to pursue opportunities according to their current availability, rather than following one’s own established preferences. It is time to ask how these departures modify the range of challenges men and women face in their life pursuits and so, obliquely, influence the way they tend to live their lives. This book is an attempt to do just that. To ask, but not to answer, let alone to pretend to provide definite answers, since it is its author’s belief that all answers would be peremptory, premature and potentially misleading. After all, the overall effect of the departures listed above is the necessity to act, to plan actions, to calculate the expected gains and losses of the actions and to evaluate their outcomes under conditions of endemic uncertainty. The best the author has tried to do and felt entitled to do has been to explore the causes of that uncertainty – and perhaps lay bare some of the obstacles that bar their comprehension and so also our ability to face up (singly and above all collectively) to the challenge which any attempt to control them would necessarily present” (pp. 1-4).

- Hugo Mercier (2020). Not Born Yesterday: The Science of Who We Trust and What We Believe.

- Mercier, the co-author of The Enigma of Reason has a new book out: “As I was walking back from university one day, a respectable-looking middle-aged man accosted me. He spun a good story: he was a doctor working in the local hospital, he had to rush to some urgent doctorly thing, but he’d lost his wallet, and he had no money for a cab ride. He was in dire need of twenty euros. He gave me his business card, told me I could call the number and his secretary would wire the money back to me shortly. After some more cajoling I gave him twenty euros. There was no doctor of this name, and no secretary at the end of the line. How stupid was I?” (p. xiii). Mercier’s, the co-author of The Enigma of Reason goal with this book: “[Y]ou should have a grasp on how you decide what to believe and who to trust. You should know more about how miserably unsuccessful most attempts at mass persuasion are, from the most banal – advertising, proselytizing – to the most extreme – brainwashing, subliminal influence. You should have some clues about why (some) mistaken ideas manage to spread, while (some) valuable insights prove so difficult to diffuse. You should understand why I once gave a fake doctor twenty euros”.

- Cailin O’Connor and James Owen Weatherall (2019). The Misinformation Age: How False Beliefs Spread.

- The authors argue that we live in an age of misinformation, an age of spin, marketing and downright lies and much of this misinformation takes the form of propaganda. How can propagandists override the weight of evidence from both direct experience and careful scientific inquiry to shape our beliefs? They emphasize that social factors are important in understanding the spread of beliefs, while also trying to describe core mechanisms by which false beliefs are spread in the hope of crafting a successful response.

- Eric Klineberg (2018). Places for the People: How Social Infrastructure Can Help Fight Inequality, Polarization, and the Decline of Civic Life.

- So far, we have focused as scholars intensively on social capital but not social infrastructure, namely the physical conditions that determine whether social capital develops. For Klineberg, “building places where all kinds of people can gather is the best way to repair the fractured societies we live in today” (p. 11).

- Daren Acemoglu and James A. Robinson (2019). The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies and the Fate of Liberty.

- Preface: “This book is about liberty, and how and why human societies have achieved or failed to achieve it. It is also about the consequences of this, especially for prosperity”. Their argument: For liberty to emerge and flourish, state and society have to be strong. Jared Diamond’s recommendation states: “One of the biggest paradoxes of political history is the trend, over the last 10,000 years, towards the development of strong centralized states, out of the former bands and tribes of no more than a few hundred people that formerly constituted all human societies. Without such states, it would be impossible for societies of millions to function. But – how can a powerful state be reconciled with liberty for the state’s citizens? This great book provides an answer to this fundamental dilemma”.

- Joel Mokyr (2017). A Culture of Growth: The Origins of the Modern Economy.

- According to economic historian Mokyr, modern economic growth depended on a set of radical changes in beliefs, values, and preferences – which he refers to as culture. He tries to explore what he describes as “the deepest questions regarding intellectual innovation. Why do people come up with new ideas? How do new ideas succeed in supplanting old ones? Why one kind of idea and not another one? By asking these questions, I will show how “early modern” Europe prepared the ground for the vast changes in the eighteenth century: The Enlightenment, the Industrial Revolution, and the rise of useful knowledge as the main engine of economic history” (Preface, pp. xiii-xiv).

- Herbert Gintis (2017). Individuality and Entanglement: The Moral and Material Bases of Social Life.

- Gintis dedicates the book to “Gary Becker, Jack Hirshleifer and Edward O. Wilson for their ability to explore deep connections across the various regions of human social life. I love these guys”. Gintis provides a rich overview of his seven themes and his 12 Chapters before he starts with the book. You can download the overview on his website or here. Don’t forget to take a close look at his final chapter The Future of the Behavioral Sciences in which he starts with the following paragraph: “I have found that when I attack problems concerning human behavior restricting myself to knowledge from a single academic discipline leaves me partially blind. I find I do much better by combining insights and models from a variety of behavioral disciplines, letting my research wander about in whatever direction seems fruitful at the moment. This book is the result of my efforts in this direction”. In a review published in the Journal of Behavioral and Experimental Economics, Eyal Winter (2017) emphasizes the importance of the book and the last chapter: “Gintis’s book is an important scientific document. Yet I am hoping that this chapter, which is more a discussion about research than pure research per se, will constitute the book’s greatest impact on the social sciences. I, like Gintis, believe that interdisciplinary research is crucial for real advancements in our understanding of social phenomena. I also believe that it is economics that has to perform most of the courtship in this relationship. Economics is often hailed or blamed for its academic imperialism. Indeed, in the past few decades it has invaded almost every discipline in the social sciences. For example, sociologists don’t have models that explain how the interest rates change, how prices equilibrate, and why some mergers take place and others don’t. By contrast, economists have models that explain how social groups form and evolve, why modern society moved from polygamy to monogamy, and why some marriages break up while others don’t. For us economists to take the lead on paving the way for interdisciplinary work in the social sciences would be the right thing to do both morally and practically. Morally, because we are the invaders; practically, because economics is primarily about incentives and we need new research incentive schemes within and across disciplines to break disciplinary chauvinism and motivate interdisciplinary research. Gintis’s book is a wonderful achievement and a must read for every social scientist” (p. 141).

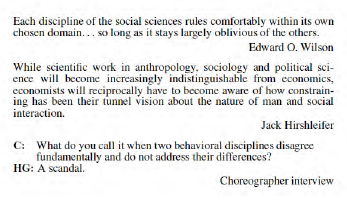

- Before he starts Chapter 12, Gintis quotes Wilson and Hirshleifer (which brings us back to his dedication):

- Praise for the book (see blurb):

- Edward O. Wilson: “Herbert Gintis is a scholar with sufficient depth in philosophy and science to develop a balanced treatment of one of the most important remaining problems in evolutionary biology: the units and forces of natural selection that yield advanced social behavior. He has done so admirably in Individuality and Entanglement.

- Kenneth Arrow: “Herbert Gintis’s new book is a major contribution to the study and unity of the social sciences. Its breadth and depth in examining the meaning and unifying power of the rational-actor model is outstanding in perceiving the fundamental issues, biological, sociological, and economic, involved in understanding the special role of human social behavior. It forces economists to analyze what rationality means and, in particular, the role of social and other-regarding forces in the development of the economy. The command of social science literature displayed is matched by the power of the formal analysis”.

- Peter J. Richerson: “Herbert Gintis is our deepest thinker about the scandalous state of fragmentation of the human sciences. In this book he distils a synthetic foundation for the sciences of human behavior from the mutually necessary but fatally flawed models offered by psychology, sociology, biology, and economics. Everyone who cares about these sciences needs to come to terms with his analysis”.

- Roman Krznaric (2020). The Good Ancestor: How to Think Long Term in a Short-Term World.

- How can we be good ancestors? Our marshmallow and acorn brain might be in a constant struggle and battle with each other. What are the ways in which we might think long? Bring on the time rebellion!

- Marcia Bjornerud (2018). Timefulness: How Thinking Like a Geologist Can Help Save the World

- Can we derive a new way of thinking that will allow us to make decisions on multi-generational timescales?

- Robert H. Frank (2020). Under the Influence: Putting Peer Pressure to Work.

- We have previously encountered Robert Frank in the 2018 Reading Group list with the books Luxury Fever and Success and Luck: he now has a new book on behavioural contagion. Throughout his career he has focused on two important questions: “How does context shape spending patterns?” and “How could genuine honesty be sustainable in even the most bitterly competitive environments?”. The arguments that he defends in this book are as Frank states (p. 23):

- Context shapes our choices to a far greater extent than many people consciously realize.

- The influence of context is sometimes positive (as when people become more likely to exercise regularly and eat sensibly if they live in communities where most of their neighbors do likewise).

- Other times, the influence of context is negative (as when people who live amidst smokers become more likely to smoke, or when neighboring business owners erect ugly signs).

- The contexts that shape our choices are themselves the collective result of the individual choices we make.

- But because each individual choice has only a negligible effect on those contexts, rational, self-interested individuals typically ignore the feedback loops described in premise.

- We could often achieve better outcomes by taking collective steps to encourage choices that promote beneficial contexts and discourage harmful ones.

- To promote better environments, taxation is often more effective and less intrusive than regulation.

- We have previously encountered Robert Frank in the 2018 Reading Group list with the books Luxury Fever and Success and Luck: he now has a new book on behavioural contagion. Throughout his career he has focused on two important questions: “How does context shape spending patterns?” and “How could genuine honesty be sustainable in even the most bitterly competitive environments?”. The arguments that he defends in this book are as Frank states (p. 23):

- Michelle Baddeley (2018). Copycats & Contrarians: Why We Follow Others … and When We Don’t.

- Capacity to copycat here, being a contrarian there. Where do we begin in understanding this complex interplay? Can economics help? What about other social sciences or biology? What are the implications for our everyday lives? Where does the group begin and end? When should we use information implicit in a group’s actions and when should we ignore it? This is a multidisciplinary account that tries to tackle those questions.

- Matthew O. Jackson (2019). The Human Network: How Your Social Position Determines Your Power, Beliefs, and Behaviors.

- Jackson – The Science of Networks powerhouse – offers this recent contribution, showing how our starting position in a network determines our power and influence, and can be powerful in understanding our lives.

- Shiller, Robert J. (2019). Narrative Economics: How Stories Go Viral & Drive Major Economic Events.

- Narrative economics is Shiller’s latest passion; he sees it as the capstone of a train of thoughts that he has been developing over much of his life. He focuses on word-of-mouth contagion of ideas in the form of stories and the efforts that people make to generate new contagious stories or to make stories more contagious as way of understanding how narrative contagion affects economic events: “We need to incorporate the contagion of narratives into economic theory. Otherwise, we remain blind to a very real, very palpable, very important mechanism for economic change, as well as a crucial element for economic forecasting” (p. xi).

- Amartya Sen (2006). Identity and Violence: The Illusion of Destiny.

- Sen shows that identity can be a complicated matter. “Central to leading a human life … are the responsibilities of choice and reasoning. In contrast, violence is promoted by the cultivation of a sense of inevitability about some allegedly unique – often belligerent – identity that we are supposed to have and which apparently makes extensive demands on us (sometimes of a most disagreeable kind). The imposition of an allegedly unique identity is often a crucial component of the “martial art” of fomenting sectarian confrontation” (xiii). “The hope of harmony in the contemporary world lies to a great extent in a clearer understanding of the pluralities of human identity, and in the appreciation that they cut across each other and work against a sharp separation along one single hardened line of impenetrable division” (xiv). We can’t miss on various books by Richard Sennet.

- Richard Sennett (2018). Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City.

- After including The Craftsman in the list 2017 and The Corrosion of Character: The Personal Consequences of Work in the New Capitalism in 2018, this is Sennett’s latest book. A Guardian article written by Joris Luyendijk entitled “Don’t let the Nobel prize fool you. Economics is not a science” encourages the initiation of a social science Nobel prize and suggests Richard Sennett as a good candidate. Building and Dwelling: Ethics for the City is Sennett’s continued studying Homo faber’s place in society, as he points out: “The first volume studied craftsmanship, particularly the relationship between head and hand it involves. The second studied the cooperation good work entails”. This book puts Homo faber in the city.

- Richard Sennett (2003). Respect in a World of Inequality.

- Preface: “The relation between respect and inequality has become my theme. As I began writing out my thoughts, I realized how much it has shaped my own life. I grew up in the welfare system, then escaped from it by virtue of my talents. I hadn’t lost respect for those I’d left behind, but my own self-worth lay in the way I’d left them behind. So I was hardly a neutral observer; were I to write an honest book on this subject I would have to write in part from my own experience. Much as I like reading memoirs by others, however, I dislike personal confession. So this book became an experiment. It’s neither a book of practical policies for the welfare state nor a full-blown autobiography. I’ve tried to use my own experience, rather, as a starting point for exploring a larger social problem” (p. xvi).

- Richard Sennett (2008). The Craftsman.

- Prologue: “Craftsmanship names an enduring, basic human impulse, the desire to do a job well for its own sake” (p. 9). This is seen as one of the key books by Sennett, one of the most interesting scholars in social sciences.

- Richard Sennet (2012). Together: The Rituals, Pleasures and Politics of Cooperation.

- Preface: “My focus in Together is on responsiveness to others, such as listening skills in conversation, and on the practical application of responsiveness at work or in the community. There’s certainly an ethical aspect to listening well and working sympathetically with others; still, thinking about cooperation just as an ethical positive cramps our understanding. Just as the good craftsman-scientist may devote his energies to making the best atom bomb possible, so people can collaborate effectively in a robbery. Moreover, though we may cooperate because our own resources are not self-sustaining, in many social relations we do not know exactly what we need from others – or what they ought to want from us” (pp. ix-x).

- Daniel S. Hamermesh (2019). Spending Time: The Most Valuable Resource

- How do we use time? Does its use vary among countries? Why do people differ in their use of time? How can economic thinking explain patterns of time use? Alan B. Krueger: “Time is our greatest gift, our dearest resource”.

- Alan B. Krueger (2019). Rockonomics: A Backstage Tour of What the Music Industry Can Teach Us About Economics and Life.

- Krueger’s last book before he died. The chorus lessons that appear throughout the book:

♪ Supply, demand, and all that jazz.

♪ Scale and non-substitutability: the two ingredients that create superstars.

♪ The power of luck.

♪ Bowie theory. “Music itself is going to become like running water or electricity… You’d better be prepared for doing a lot of touring because that’s really the only unique situation that’s going to be left”.

♪ Price discrimination is profitable.

♪ Costs can kill.

♪ Money isn’t everything.

- Talcott Parsons (1977). The Evolution of Society (edited by Jackson Toby).

- It is worth taking a look at the work of Talcott Parsons, the famous American sociologist. Neil Smelser said of him28: “One of the maxims that my teacher and friend Talcott Parsons was fond of repeating was this: in dealing with any theoretical topic, it never fails to repay one’s efforts to go first to the great classical thinkers on that topic. Parsons himself observed that principle repeatedly, revisiting and recasting the original insights of Durkheim, Weber, or Freud as he continued his lifelong struggle to conquer the mountainous obstacles to systematic sociological theory”29.

- Michael Batty (2018). Inventing Future Cities.

- Can anything about cities be predictable? What is predictable and what is not? What are the conditions under which prediction might take place? Batty writes: “It is now widely accepted that social systems and cities are more like organisms than they are like machines. In this sense, they are the product of countless individual and group decisions that do not conform to any grand plan. These actions lead to structures that are self-organizing and exhibit emergent behaviour” (p. 5).

- Jane Jacobs (1961). The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

- Jacobs in her introduction: “This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding. It is also, and mostly, an attempt to introduce new principles of city planning and rebuilding, different and even opposite from those now taught in everything from school of architecture and planning to the Sunday supplements and women’s magazines. My attack is not based on quibbles about rebuilding methods or hairsplitting about fashions in design. It is an attack, rather, on the principles and aims that have shaped modern, orthodox city planning and rebuilding.

- Monica L. Smith (2019). Cities: The First 6,000 Years.

- Praise by Edeward Glaeser: “A panoramic guide to our earliest urban areas, places that seem both so foreign and so familiar. Monica Smith’s fascinating description of the many millennia of city building should remind us that we are an urban species. The cities that Smith describes faced many of the same challenges as our cities today, and the lessons of the past remain important today. This is a rich treatment of the growing and important field of urban archaeology, which continues to yield new surprises and insights that matter for city making today. Cities are responsible for many of the best things that humankind has achieved – Monica Smith tells the story of how we built the cities that made everything else possible”.

- David Berlinski (2019). Human Nature.

- Berlinski: “This book ranges over many topics, and incorporates a number of different styles, but is unified, I think, by a common concern for what is an indistinct concept, and that is the concept of human nature. It is a concept severely in disfavor because it suggests that there is something answering to human nature, some collocation of ineliminable and necessary properties that collectively define what it is to be a human being. There are such properties. Of course there are. That men are men is an obvious example. Men are men is true because men are necessarily men. And the fact that there are such properties does involve a commitment to essentialism. No one disposing of essentialism in biology is disposed to disregard it in logic, mathematics, physics, or ordinary life. Human beings are not indefinitely malleable. There are boundaries beyond which they cannot change. We are not simply apes with larger brains or smaller hands, and the distance between ourselves and our nearest ancestors is what it has always appeared to be, and that is practically infinite. Human beings are perpetually the same, even if in some respects different” (pp. 15-16). Some topics: Violence (The First World War; The Best of Times; The Cause of War), Reason (Relativism- A Fish Story; The Dangerous Discipline; Necessary Nature; Disgusting, No?; Majestic Ascent: Darwin on Trial; Memories of Ulaanbaatar; Inn Keepers), Fall (The Social Set; Godzooks), Personalities (A Flower of Chivalry; Giuseppi Peano, Sonja Kovalevsky; A Logician’s Life; Chronicles of a Death Foretold), Language (The Recovery of Case); Places (Prague, 1998; Old Hose; Vienna, 1981).

- David Gelernter on David Berlinski: “Berlinski is a modern Hannah Arendt, but deeper, more illuminating and wittier (i.e., smarter). His ability to use science and mathematics to illuminate history is nearly unique. If I were assembling a list of essential modern books for undergraduate at my college, this book would be number one. Not only would students learn a tremendous lot form this book; many would also love it. Likewise their teachers. Berlinski’s gift to mankind is gratefully received”.

- Howard Gardner (2006). Changing Minds: The Art and Science of Changing Our Own and Other People’s Minds.

- Even before the book was published, Gardner was surprised to receive a phone call from the office of Ralph Nader, who was launching his campaign for president… Next came invitations from an advertisement agency, an academic-corporate collective seeking to change the fast-food eating habits of obese Americans, and a high-level commission on national security, charged with altering the beliefs and work habits of their officers. Well, there is certainly a demand for Changing Minds 😉😉…

- Robert Cialdini (2016). Pre-Suasion: A Revolutionary Way to Influence and Persuade.

- Pre-Suasion is Cialdini’s follow up book to Influence. His note: “Pre-Suasion seeks to add to the body of behavioural science information that general readers find both inherently interesting and applicable to their daily lives”.

- James G. March (2010). The Ambiguities of Experience.

- March is the author of several important books, such as A Primer on Decision Making, Organizations, The Pursuit of Organizational Intelligence, A Behavioral Theory of the Firm or the enjoyable On Leadership. In this book, he focuses on the role of experience in creating intelligence in organizations and beyond.

- Thomas Schelling (1980). The Strategy of Conflict.

- Commitment in order to influence! According to Schelling this may be his most important idea, and the book Strategy of Conflict his most important scholarly contribution (see here an interview (Harvard Kennedy School Oral History), Chapter 22: Contributions to Scholarship and Public Policy, 1:06:06-1:09:27).

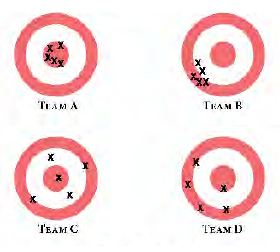

- Daniel Kahneman, Olivier Sibony, and Cass R. Sunstein (2021). Noise: A Flaw in Human Judgement.

- Team A: Ideal world

- Team B: Biased, systematically off target

- Team C: Noisy, shots widely scattered. No interesting hypothesis. Members are poor shooters.

- Team D: Biased and noisy (many organisations are afflicted by both).

- The authors’ message: “To understand error in judgement, we must understand both bias and noise”. Why such a book? Well, noise is rarely recognized (usually offstage) while bias has been the star of the show despite the fact that the amount of noise is quite high in the real world. From the authors: “Understanding the problem of noise, and trying to solve it, is a work in progress and a collective endeavor. All of us have opportunities to contribute to this work. This book is written in the hope that we can seize those opportunities” (pp. 9-10).

- Michael J. Sandel (2010). Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do?

- Back cover: “Is it always wrong to lie? Should there be limits to personal freedom? Can killing be justified? Is the market fair? What is the right thing to do? An attempt to assess the core theories of justice based his famous Harvard course.

- Yakov Ben-Haim (2018). The Dilemmas of Wonderland: Decisions in the Age of Innovation.

- Can this book provide a guideline for managing and thinking about the implications of the challenge of innovation dilemmas, the decisions to use or not to use new and promising but unfamiliar and therefore uncertain innovations?

- Kenneth E. Boulding (1961). The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society. University of Michigan Press.

- “Behavior depends on the image – the sum of what we think we know and what makes us act the way we do”. Boulding was one of the greatest social scientists of the 20th century, forgotten by many economists despite having won the John Bates Clark Medal. In this book, he proposes a new science.

- W. Brian Arthur (2009). The Nature of Technology: What It Is and How It Evolves. Free Press.

- Arthur, is one of the most creative minds in economics and a member of the Founders Society of the Santa Fe Institute. In this important book he applies biological thinking to understand the nature of technology.

- Thomas C. Schelling (2006). Micro Motives and Macro Behavior. W. W. Norton.

- A classic by Nobelist Schelling (cited more than 6500 times (Google Scholar)). A good foundation for Agent-Based Computational Modelling.

- Claude Lévi-Strauss (2013). Anthropology Confronts the Problems of the Modern World.

- First translation of a series of lectures given by Lévi-Strauss in 1986, synthesizing his major ideas about structural anthropology.

- Robert Trivers (2011). The Folly of Fools: The Logic of Deceit and Self-Deception in Human Life.

- The powerhouse of Trivers approaches a still poorly understood topic applying an evolutionary approach. Trivers: “When I say that deception occurs at all levels of life, I mean that viruses practice it, as do bacteria, plants, insects, and a wide range of other animals. It is everywhere. Even within our genomes, deception flourishes as selfish genetic elements use deceptive molecular techniques to over-reproduce at the expense of other genes. Deception infects all the fundamental relationships in life: parasite and hosts, predator and prey, plant and animal, male and female, neighbor and neighbor, parent and off-spring, and even the relationship of an organism to itself” (p. 7).

- Roger C. Schank (2016). Education Outrage.

- The creative Schank “has had it with the stupid, lazy, greedy, cynical, and uninformed forces setting outrageous education policy, wrecking childhood, and preparing students for a world that will never exist. His keen intellect, courage, and razor-sharp wit cuts away several layers of conventional wisdom, causing readers to confront their own prejudices and school-distorted notions of learning. No sacred cow is off limits – even some species you never considered” (back cover).

- Joseph Henrich (2020). The Weirdest People in the World: How the West Became Psychologically Peculiar and Particularly Prosperous.

- Henrich’s latest contribution. He saw the previous book The Secret of Our Success (included in the first session in this year’s reading group) as part of the journey that led to this book: “Originally, the ideas that I developed there were supposed to form Part I of this book. But, once I opened that intellectual dam, a full book-length treatment flooded out, and nothing could stop it. Then, with The Secret of Our Success tempered and ready, I could confidently synthesize the elements necessary for this book:

- If you are interested in watching him in action, see here his presentation at the UBS Center.

- (2016). Homo Deus: A Brief History of Tomorrow.

- A look at future challenges, and where we are or might be going with respect to tackling the big questions.

- Kevin Kelly (2016). The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces that Will Shape Our Future.

- Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired has a great intuition for making sense of technology.

- Herbert Simon (1997). Administrative Behavior: A Study of Decision-Making Processes in Administrative Organizations.

- Still a timeless roadmap for understanding organizations and a must read for any social scientist.

- Albert O. Hirschman (1991). The Rhetoric of Reaction: Perversity, Futility, Jeopardy.

- In the Preface to the book, Hirschman writes: “[c]oncern, stubborn, and exasperating otherness of others is at the core of the present book”; this is a “cool” historical and analytical examination of surface phenomena such as discourse, arguments, or rhetoric.

- Anthony Brandt and David Eagleman (2017). The Runaway Species: How Human Creativity Remakes the World.

- According to the authors, engineers and artists innovate by the same means: bending, breaking and blending what they know. Novelty also requires resonance with one’s society. Thus, creativity is an inherently social act, or as the authors put it “an experiment in the laboratory of the public” (p. 114). You are therefore faced with a dilemma, whether “to create something that sticks close to the familiar, or something that breaks new ground?”. Is there evidence for universal beauty? Which row in the image below elicits the strongest brain response? According to Gerda Smets who ran experiments, it is the pattern in the second row (at around 20% level of complexity). Brandt and Eagleman explore “our need for creativity, how we think up new ideas, and how our innovations are shaped by where and when we live”. They explore key features of creative mentality and illustrate how to foster creativity: “a dive into the creative mind, a celebration of the human spirit, and a vision of how to reshape our worlds” (p. 10).

- Tim Harford (2016). Messy: How to Be Creative and Resilient in a Tidy-Minded World.

- This was one of the favourite books of the 2017 Mammoth Reading Group. Time to revisit it again.

- Deborah L. Rhode (2018). Cheating: Ethics in Everyday Life.

- Chapter 1: “In 1990, the year of Milken’s sentencing, his alma mater, the Wharton School, featured a parody of its graduation ceremony. The student playing the class valedictorian stepped away from the podium and sang about how she achieved that role. In lyrics set to the tune of Michael Jackson’s hit song, “Beat it,” she explained:I cheated, cheated,

Cheated, cheated,

And maybe I sound conceited,

You’re probably angry,

I’m overjoyed.

I work on Wall Street,

You’re unemployed.

I want a good job

Who cares if it’s right?

To hell with ethics

I sleep at night. - Cheating happens in sports, organizations, taxes, academia, insurances and mortgages, or marriage. Rhode argues that cheating is deeply embedded in everyday life. Her plaidoyer: “Our culture needs to send a different message and in her book she tries to suggest also why and how”.

- Chapter 1: “In 1990, the year of Milken’s sentencing, his alma mater, the Wharton School, featured a parody of its graduation ceremony. The student playing the class valedictorian stepped away from the podium and sang about how she achieved that role. In lyrics set to the tune of Michael Jackson’s hit song, “Beat it,” she explained:I cheated, cheated,

- Daniel Oberhaus (2019). Extraterrestrial Languages.

- Are we ready to talk to an alien? How should we talk to aliens? What aspects of the faculty of language are necessary for language as such? Is extraterrestrial cognition sufficiently similar to our own?