Landscape as Place

by Kevin Wilson

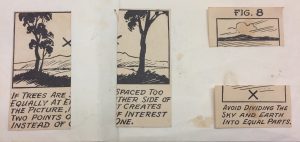

Some 30 years ago as a photography student, l was obsessed with conceptual questions around so-called principals of what makes a good landscape image. I dwelled more on the ‘don’t dos’ as opposed to the ‘dos’ as is evident in my journal at the time.

Today the question of how we represent the landscape is still uppermost in my work. But rather than being only an aesthetic consideration, it has been tempered by my own broad experience of landscapes, a greater understanding, through conversation, imagery and design, of how the people who live in those landscapes see them, and the concept of place.

Last year during a visit to Tambo, a small town in Western Queensland, l was invited by a passionate local farmer Jenny Skelton to explore her cattle property. I had been to Tambo many times before and had, in 2012 over six months, curated a major public art residency and exhibition Project (i).

As Jenny drove me around for hours on the massive property l was intrigued and captivated by her love of the land but more importantly her focus on elements of the landscape that she saw clearly, but which l found hard to isolate in what appeared to be a flat and expansive vista crowned by an endless sky of clouds. I started to think about place and its role in determining who we are, or “how the stuff of our inner lives is found in the outer places in which we dwell” (ii). Will l understand this person through the landscape or the landscape through the person?

My own personal disconnect from this landscape reminded me of the words of Wendell Berry:

“once we see our place, our part of the world, as surrounding us, we have already made a profound division between it and ourselves”(iii).

Admittedly this was not my place, but as an artist my divisive relationship to the land was to try and capture it as an aesthetic object. My landowner guide was definitely part of that landscape. In describing this place, the most powerful representation of it was not an image but the memory of the passionate words that flowed from her mouth and drew lines in the landscape.

More recently l was asked by Winton artist, Karen Stephens, to write about her upcoming painting exhibition titled Fishing for landscape. How would she interpret a landscape dominated by wide horizon lines and vast swathes of sky and flat earth? Would she take an expansive abstracted approach like Fred Williams or Tim Storrier? What l found was an artist totally focused on the small zone in front of her, almost what was at her feet, even though she was still incorporating all the land and sky she could see.

In Stephens’ works there is a restructuring of place taking place. It is no longer about capturing the landscape but actually being inside it – in a place where the body slips away and the act of painting is about the pure experience of being in that place. A darkness or murky depth is pervasive suggesting much that is not known but which also acts as a kind of backdrop to the activity on the surface.

She calls this ‘scratching in the dark‘ and aligns her activity as a painter to her forebears who were opal miners. This alignment not only suggests a search for something perfect and valuable but also the difficulty and solitary nature of each profession. But perhaps more importantly Stephen’s use of verbs, which at times are actually written on the paintings, such as fishing, mining, and projecting to define her vision reveal more about the incorporation of her family history and the landscape of her own mind as a determinant of place.

Individuals can express their connection and understanding of place through multiple channels, not just through conversation or artistic practice. However, determining a community’s sense of place, of itself and its needs has not always been clearly articulated by the community or understood by those outside it. This is particularly so when it comes to arts and culture. How do a town’s own residents determine the kind of cultural expression they want to represent their town? This was the question l asked when developing Art in the Grasslands, the public art project that took place in Tambo in 2012.

Art in the Grasslands was a participatory public art project without the directive to make physical artworks. By living in the community, artists were able to meet a broad range of locals and engage in dialogue and friendship with them. In an interview with Grant Kester, artist Peter Dunn described these kind of artists as “context providers rather than content providers” (iv). Each artist had a different process and engaged with various cohorts of the community. From this residency program artists generated a range of ideas for public art that responded to community aspirations and sense of place. These ideas were then given back to the community to digest and use as they wished.

In participatory art practice, both artists and non-artists alike can be involved at various stages of the development of an artwork from ideation through process to the making of art works. It emerged from a desire to democratize artmaking rather than it being made by a chosen few, initially with the community arts movement in the 1970s and the fine art world in the 90s and beyond. Claire Bishop described the spectrum of this new practice as “socially engaged art, community-based art, experimental communities, dialogic art, littoral art, interventionist art, participatory art, collaborative art, contextual art and (most recently) social practice”(v). Of course, labels like these have a whiff of art world jargon.

Perhaps of more relevance to the cultural construction of place and identity is the concept of creative placemaking that emerged from community arts practice. It was, not surprisingly, adopted by governments, given its concrete manifestation in infrastructure, to improve physical community spaces based on an understanding of the community’s sense of identity. Unfortunately, creative placemaking quickly became a form of gentrification of space.

Increasingly there is now a move away from the ‘improvement’ of physical spaces back to a focus on people and an understanding of psychosocial processes which include, according to Courage and McKeown, “comprehension of self and other, inclusion and exclusion in processes and systems that affect feelings of belonging”(vi).

Just how this is achieved and by whom opens up a whole new field of praxis. Participatory art practice and its methodologies reflect to some degree a new way of working for artists that enters into this psychosocial space. Although it could be argued that, like in the early days of community arts practice, there is a danger that the artist will determine and structure the art making process and thereby deny a community the opportunity to set its own direction based on an understanding of its own identity.

Margo Handwerker begins to address this danger in A rural case – Beyond creative placemaking when talking about her own collective’s, M12, connective practice in rural communities.

It weaves “a range of expertise to realize a range of creative outcomes, whether a workshop, a book, a record, radio programming, or a physical space. Motivated by care and concern, individuals with varying kinds of knowledge, whether artistic, regional, scientific, etc., come together to create something of mutual interest and shared effort. Conceptualizing and executing projects through collaboration with various stakeholders is key to our connective aesthetic, and forging these relationships takes time”(vii).

When looking back at Art in the Grasslands, a connective practice was evident in the residency model but essentially the community did not participate in creative production. In the years since the project took place a small number of public art projects have been realized, but again they have essentially been cherry picked by the community from the ideas artists proposed at the end of their residencies. So, for those creatives working in communities, in what ways then can the development of art practice by the community itself be nurtured and grown? And what role does the itinerant artist play within a community? Indeed, how does art define itself differently from social work? In the broader context of government and policy development Handwerker also poses these questions:

“How is a community’s interest determined and by whom? How is improvement – a relative term – determined? How do we judge transformation as successful or unsuccessful? How do we measure whether or not character and quality are shaped? How does framing the field in these terms impact the artists, the places, and the funders who participate? How are the missions and methods of such disparate participants impacting our field?”(viii).

These are important questions but in the meantime people in regional communities are defining their own sense of place and love of the landscape. The more we know about the uniqueness of a farmer or artist’s vision and indeed the vision of others in the community, and of course the ability of the community to represent place, then the less we need of culturally embedded aesthetic rules.

Materials referenced:

- Tambo Public Art Residency and Exhibition Project – Art in the Grasslands

- Malpas, J. (2018). Place and Experience. London: Routledge, p.6

- Berry, W. quoted in Lippard, L.R, Looking around: where we are, where we could be. In Lacy,S (Ed), Mapping the Terrain: new genre public art (p.114-130), Bay Press. P.116

- Kester, G. (2013).Conversation pieces : community and communication in modern art . Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.1

- Bishop, C. (2011). Artificial hells : Participatory art and the politics of spectatorship. Verso. p.7

- Courage, C., & McKeown, A. (2019). Creative placemaking : research, theory and practice . Routledge.p.4

- Handwerker, M.(2019). A rural case – Beyond creative placemaking in Courage, C., & McKeown, A. (2019). Creative placemaking : research, theory and practice, 89

- Handwerker, M.(2019). A rural case – Beyond creative placemaking in Courage, C., & McKeown, A. (2019). Creative placemaking : research, theory and practice, 84

Kevin Wilson is a PhD candidate at Queensland University of Technology. He began his art career in Melbourne as a photographer and has artworks in the National Gallery of Victoria and RMIT collections. He has extensive experience in regional communities both in the areas of education and art as a community worker, art gallery director and curator.

Kevin Wilson is a PhD candidate at Queensland University of Technology. He began his art career in Melbourne as a photographer and has artworks in the National Gallery of Victoria and RMIT collections. He has extensive experience in regional communities both in the areas of education and art as a community worker, art gallery director and curator.

It’s interesting how your environment can change your focus on what is important. I never did landscapes before coming to Gympie.

Hi Joolie, would be great to hear more about how the landscape fed into broader concepts around sense of self And place

A very interesting area to write about! People on

Land know it backwards at all times of year and under all conditions plus what’s coming and going within the land. It becomes part of oneself.

Hi Kevin. A group of artists /writers and others: Gunggari,Bidjara and local community and visitors are involved in an evolving sustained project in Mitchell. Ever changing especially now with covid Myself and others are facilitating this project I’ll be interested in your research.

Hi Kevin,

I’ve thoroughly enjoyed this post and found myself facing many of the same questions when completing my masters research project: Rockpocalypse – reconceptualising applied theatre practice through the gift of the game. In my own PLR, I similarly was looking for a way of navigating the development of a place-based, curated, creative product (in this case, a work of theatre) in dialogue with community, and I too found that previous approaches tended to prioritise the artist-in-residence model over a more active, agentic one for community members. What I ultimately developed was a twofold praxis, whereby I developed a live-action roleplaying game to engage theatre-averse/ambivalent members of the Rockhampton community. The player-generated narrative outcomes of these game sessions then formed the research basis for my playwrighting process. I’m continuing to explore approaches to navigating the porous audience/creator relationship now as I begin my PhD (where I will also be working with rural/regional communities in Central Queensland).

I’m quite passionate about the need for our sector to find a middle way, engaging communities as makers and contributors to locally-responsive work for which they hold a sense of ownership and investment. I’m excited to follow the Regional Arts and Social Impact project as you continue to develop your findings and research output.

Thanks for a thought-provoking read!