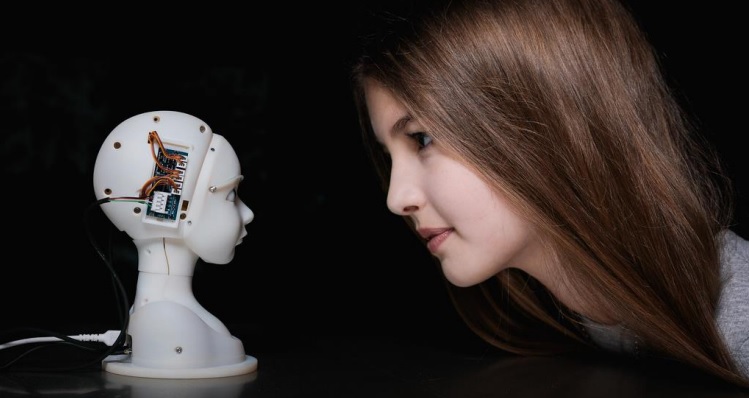

Our Emotional Connection to Service Robots

The AI revolution is already upon us, with digital assistants transforming the way we access information and personal robotics automating tasks long thought to be too complex for machines to handle. While the majority of robots still undertake purely mechanical tasks, from self-driving cars to automated cleaning and lawnmowing robots, increasingly robots are being brought into the service industry to undertake social tasks. Massive advances in AI natural language processing are powering this change, allowing humans to interact and give commands to robots conversationally rather than through coding. This more naturalistic interaction brings robots from the backstage (manufacturing and logistics) and into the frontstage of businesses, directly interacting with employees and customers.

The AI revolution is already upon us, with digital assistants transforming the way we access information and personal robotics automating tasks long thought to be too complex for machines to handle. While the majority of robots still undertake purely mechanical tasks, from self-driving cars to automated cleaning and lawnmowing robots, increasingly robots are being brought into the service industry to undertake social tasks. Massive advances in AI natural language processing are powering this change, allowing humans to interact and give commands to robots conversationally rather than through coding. This more naturalistic interaction brings robots from the backstage (manufacturing and logistics) and into the frontstage of businesses, directly interacting with employees and customers.

These new service robots recognise specific voices, can discern emotional states from facial expressions and converse naturally with humans, allowing them to provide highly customisable services for customers. In most service settings, these robots work at the intersection of digital, physical and social realms, providing a conversational interface with digital information that is much more accessible than a typical user interface. This makes service robots ideally suited for customer service roles, with these machines deployed as waiters, receptionists, and companions.

This dramatic change in the range of tasks being automated often stirs complex emotions in the humans now interacting with service robots. The increasing agency and autonomy of these machines causing us to question our own agency and autonomy. There are also concerns that the quality of service able to be provided by a robot is inherently less than that of a human, given the human capacity for creativity that is often required for successful service interactions. While these new social robots provide the possibility of great utility to the service industry, the complex emotional response they provoke makes it important for retailers to understand what is underpinning our relationships with robots.

Approach or Avoid?

While most humans readily recognise the utility of service robots, the complex and competing emotions they provoke often hinder out desire to interact with or collaborate with these machines. These motivational conflicts are created by competing desires, beliefs, and perhaps most importantly, emotions. For instance, an employee may feel happy when the robot makes their job easier but angry if they feel their job is now threatened. A consumer may be happy with the novel experience of being served by a robot but frustrated when the robot does not respond in an expected way.

Research into the applications of existing service robots reveals the scope of this conflict: In healthcare service robots are appreciated when monitoring patients, but not in keeping them company; In military applications, robots are accepted for rescue but not surveillance roles; In education, robots are considered well suited for STEM subjects, but not social sciences and arts. Managers in these settings often resolve these conflicts on an ad hoc basis by setting “boundary conditions” for the service robots, only assigning them to tasks that the humans they interact with feel they are best suited for.

However, it is not always easy to simply avoid these motivational conflicts in this way. For example, if an employee both wants a robot that can make their job easier but does not want a robot that can replace their job, it may be difficult to design a service robot that only takes on the tasks the employee wishes it to – especially when the robot is capable of completing a wider range of tasks.

Often these conflicts are the result of cognitive bias, with employees and customers feeling that robots are better or worse suited to particular tasks on the basis of emotional rather than rational beliefs. In challenging these biases, robotic designers can build features into robots that directly refute these emotional beliefs. For example, designing robots that deliberately make mistakes such as forgetting names in a distinctly human way, makes the robot feel fallible and a little more like “us”.

The Tipping Point of Trust

Resolving this conflict between the desire to use and avoid using service robots will depend on how managers are able instil trust in this technology.

Trust involves both rational and emotional decision making, resulting in the belief that a robot will act in own best interests. While the functional performance of these robots will be a crucial component of this decision, the emotional component of human-robot interaction cannot be overstated. This emotional component is not simply a matter of cognitive bias, but also of perceived intent. An employee that distrusts management is more likely to perceive a service robot as a threat to their employment, regardless of the functional characteristics of the robot itself.

These previously held beliefs about the role and capabilities of a robot are an important source of confirmation bias when it comes to interactions with robots, with both employees and customers evaluating a robot’s performance in line with their previous expectations of it. Managers seeking to integrate service robots into retail business must consider this and build trust with employees and customers long before actually deploying robotic assets.

Service robots will undoubtedly play an important role in the future of retail, capable of integrating digital information and data analysis in a way that no human ever could. Despite the tremendous utility they provide however, managers must recognise that emotional reactions to robots, often based on external factors and cognitive biases, will drastically influence how trusted these machines are by employees and customers. Proactively addressing these concerns and changing the narratives around what a robot can and can’t do is therefore a critical first step in integrating these machines into retail.

Researcher

More information

The research article is also available on eprints.