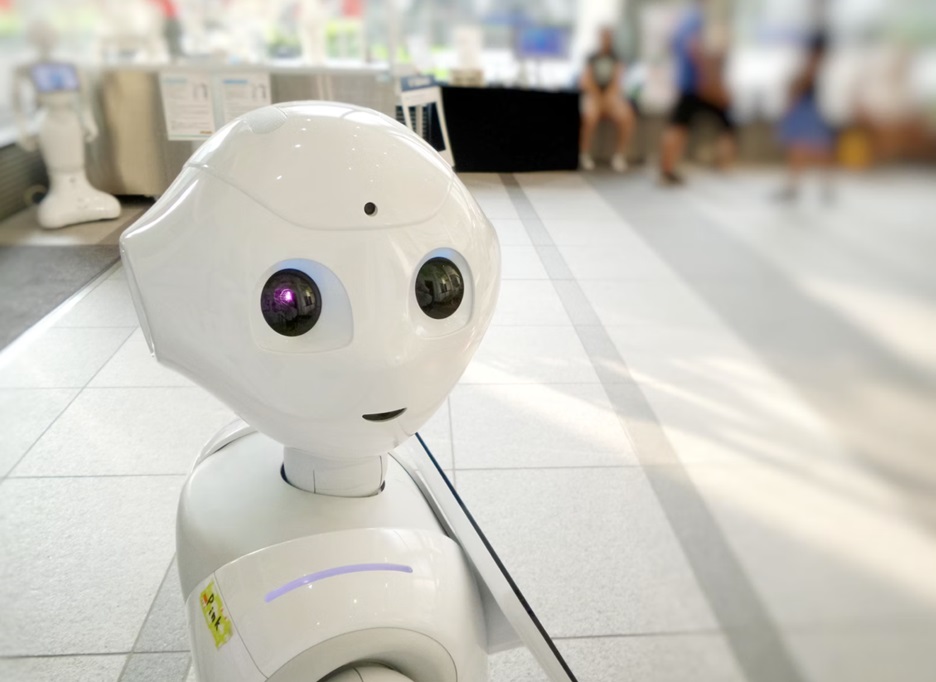

From 2020 to 2025, the market size for service robots is likely to spike from $37 billion to over $102 billion. As more and more service environments adopt service robots to interact and service customers, they will soon become an integral part of frontline service operations in different industry sectors including healthcare, hospitality, and retail. Such intelligent technologies can enhance service operations, for example, with their ability to communicate with customers or store and analyse data.

However, the reality is that these robots can either work alongside frontline service employees (FSEs) or completely replace their jobs. Findings from recent surveys reveal mixed reactions from human employees. Some may perceive threats to their job and feel uncomfortable working with a robot, while some others would trust a robot coworker. As prior research suggests that employees’ collaboration with technology is key for a company’s success, there is a need to investigate how humans and AI-enabled technologies such as service robots can coexist and collaborate.

To fill this gap, this study explores frontline employees’ perceptions of collaborative service robots (CSR) and proposes the concept of willingness to collaborate (WTC), drawing on appraisal theory. By focusing on frontline service operations, it also contributes to the limited research on human-robot collaboration, which were mainly in manufacturing settings.

Method and sample

This qualitative, exploratory study consisted of semi-structured, problem-centred interviews to gather insights on individual employee’s perception of integrating technology into the workplace. Purposive sampling was used with two selection criteria: participants should (1) have experience with service robots and (2) be working in the service industry. Participants were contacted through personal contacts and LinkedIn. The final sample consisted of 36 interviewees aged 24-61 with various professional backgrounds.

The interviews contained four sections to provide structure and guideline: (1) general knowledge and experiences with CSRs, (2) perceived influence of CSRs on the working environment and individual attitudes toward CSR, (3) willingness to collaborate with CSRs, and (4) future developments and scenarios of human-robot collaboration. They lasted 40-90 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed for thematic analysis on NVivo.

Key findings

The findings start with a discussion of attributes of the robot, the job environment, and the employee.

- CSR attributes

- Autonomy: Some FSEs like that robots can independently perform tasks, while others do not think CSRs can provide satisfactory information and service. Respondents also viewed CSRs’ autonomy as a threat to their jobs and express fear because robots have no morals nor understanding of appropriate behaviours in social interactions.

- Social presence: FSEs appreciated the interpersonal interactions and exchanges with human colleagues but felt difficult to image this with robots because of their low social presence.

- Humanoid appearance: In the service context, robots usually take on human features and appearance to build trust and facilitate interaction with customers. But employees may also feel the resemblance to humans is too great and have wrong expectations.

- Job attributes

- Job type: Employees were aware of potential changes at the organisational frontline and that some types of jobs may be taken over by robots in the future, for example simple repetitive tasks, tasks with high physical load, analytical tasks, or even customer contact tasks.

- Job demands: Many respondents were aware that in the future job demands will change. Some were afraid that they cannot keep up with and meet requirements for technical skills, such as how to operate a robot properly.

- Job roles: Respondents acknowledged the changing working structures and possibly hierarchies within service organisations. Employees demand clear structures and see themselves in the more important roles and positions compared to robots.

- FSE attributes

- Individual characteristics: Employees’ willingness to collaborate (WTC) with service robots depend on their individual characteristics. For example, some were curious and open to try out the new form of collaboration while others were more hesitant and less enthusiastic. Some also like to work in teams while others prefer to complete task on their own and refuse assistance in any form.

- Technology readiness: If FSEs have had prior experience with technology in other contexts, they might have higher WTC with robots in professional service contexts.

- Robot bias: Respondents reported mixed feelings regarding collaborating with CSRs. Many were doubtful because implementing CSRs can decrease chances to collaborate with human colleagues, share knowledge, and prompt innovations. However, they also acknowledged that CSRs could provide support with tasks and increase productivity. Employees should also have a choice to work voluntarily with a robot by having multiple technology options or different levels of automation.

The findings also involve positive and negative outcomes that respondents expect from working with a CSR. Positive appraisals include CSRs’ resilience, ability to deliver consistent performance, and improved efficiency as robots are not influenced by mood, physical, and mental conditions, and do not experience fatigue. Therefore, FSEs appreciate the ability to delegate physically demanding or repetitive tasks to robots and feel more empowered. They may also perceive interactions with CSRs as a form of social relationship building, like interacting with human coworkers. Negative appraisals of CSRs include FSEs’ difficulty to establish trust in the technology, lack of technical knowledge or competencies to use the technology, lack human coworkers to build personal relationships, fear of being replaced by a robot, and risks of data security and surveillance.

In addition to the cognitive appraisal of benefits and risks related to CSRs, this study finds a second stage of secondary appraisal in which employees develop coping options that correlate with their levels of WTC with service robots. An underlying dilemma for collaborating with robot coworkers is a trade-off between human’s level of control and robot’s level of autonomy. Almost all respondents expressed a strong desire to control the robot, which was a basic prerequisite for working with CSRs. They wanted a clear set of rules for the collaboration and a clear role distribution. All respondents also emphasised that human employees would always have the superior role and robots would “just” support and take over subordinate roles but should not make autonomous decisions.

From these stages of primary and secondary appraisal, four personas emerge, which represent employee’s degree of WTC (Figure 2).

- Embracer personas fully cooperate with CSRs and integrate unique skillsets of humans and service robots to improve efficiency and create value.

- Supporters appreciate the benefits of the technology and use it to reduce their workload by taking away tedious and repetitive tasks, but still want to remain in control.

- Resisters refuse to interact with CSR and complain to managers about the implementation of CSRs, but they have gathered at least some kind of experience with technology in either private or professional situations.

- Saboteurs have had no experience with technology, refuse to cooperate, and also actively prevent the implementation of it.

Recommendations

This study is useful for companies seeking to integrate service robots into their frontline work processes. It is recommended that strategies are developed to reduce employees’ perceived risks in areas of job demands and resources to balance levels of autonomy and control. Managers should pay attention to selecting CSR attributes to match the job and employee attributes of the company. Specifically, clear rules and roles for the collaboration process should be specified to reduce opposing attitudes and retain perceived control and perceived superiority over service robots. CSRs should also be introduced gradually into the work process to ensure technology readiness and reduce FSEs’ perceived loss of control, for instance, by integrating a “simpler” CSR for collaboration and introducing the benefits of the technology before moving on to more capable and autonomous CSRs in the future. Managers should also identify key decision makers and their WTC with CSRs and develop strategies to turn them into enablers if they constrain the implementation of the technology. In general, this study emphasises that CSRs should be seen as an opportunity to improve service processes and the work environment of FSEs, so that talented employees are retained in the long term. Ultimately, companies that motivate their employees to collaborate well with CSRs will gain the most benefits from the human-robot interaction and the opportunities this brings in the context of the frontline service workplace.

Researcher

More information

The research article is also available on eprints.